Greene, Molly (2000) Beyond the Northern invasion: the Mediterranean in the seventeenth century, Past and Present, 174, 41-70

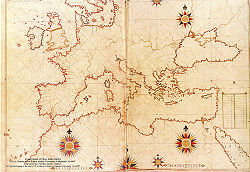

At least since Fernand Braudel, the 17th century is supposed to be the moment the moment the Northern Europeans (English, Dutch and later French) ‘invaded’ the Mediterranean pushing aside effortlessly the old regional powers Spain, Venice and the Ottoman Empire. In this article, Molly Greene shows that it was not that simple, nor one-sided (p.42).

Power vacuum

The traditional Mediterranean naval powers did lost their dominant position in the late 16th century. For instance the Venetian merchant marine was cut in half between 1550 and 1590. But the French were too weak due to internal turmoil and the Dutch and English too distant to fill the power vacuum (p.43). It proved a fertile environment for pirates and lesser powers such as Malta created a climate of constant violence on the sea (p.45). Commercially smaller players thrived, in particular the Greeks (p.48).

The Greeks assumed a lead role in the coastal traffic in the eastern Mediterranean (a trade called ‘caravane’). But they also took over the declining Venetian shipping industry in the Adriatic and Aegean seas and Greek merchants even reached Flanders (p.49).

The Greeks, as Ottoman subjects, particularly benefited from the safety the openness of the Istanbul market to them. Meanwhile the Ottoman Muslim merchants enjoyed a monopoly over the trade in the Red and Black seas as they were off limits to foreigners (p.50). They also seized many opportunities in the various trades between Egypt and Anatolia (grain, wood; p.52).

Finally local Italian and North African players were very active in various trades between Europe and Maghrib in particular from, to and through Livorno.

‘Awkward sea to sail in’

In the Mediterranean anarchy search for an adequate protection was paramount to trader. Unlike what the commonly used lexicon of Holy War could let us believe, there was no strict religious divide. Merchants from a religion were often protected by governments of another religion, while pirates regularly attacked coreligionists (p.52).

“Certain apparently impermeable boundaries were actually crossed with some regularity and little fuss” (p.53). For instance, the English captains were forced by treaty to defend their Muslim Tunisian passengers against Christian pirates (p.54).

To make matters a bit more complicated, the interests of the various players within a same nation often differ widely. For instance, in the Levant the French merchants often opposed the diplomats or the missionaries. At one point the French ambassador was also at the same time envoy of the pope and representative of the merchants (p.55). On top of that, he often disregarded direct orders and accepted briberies from various local players (p.56).

Where to draw the line?

Merchants from various origins also commonly get into business partnerships. French merchants lent their names to Jewish and Muslim ones so that their wares would not be seized by the Maltese corsairs (p.58). The Greek orthodox living under Muslim rule were themselves commonly targeted by Christian privateers but were regularly protected by the Pope or the King of France and could even sue their attackers in Malta’s ‘Tribunal Armamentorum’ (p.60).

In Greece, Muslim and Christian commonly shared ownership of a boat. Many ships were also Muslim-owned but Christian-manned. Muslim businessmen commonly vouched for their Christian counterparts in Ottoman courts (p.61).

Finally, Christian were commonly converting to Islam, but as this conversion was sometimes forced, Westerners commonly failed to differentiate the ones from the others (p.61).

Getting more peaceful

In the 17th century, Muslim corsairs did not attack Christians indiscriminately. They respected merchants and cargoes of those European states they had a peace treaty with (p.62). Of course there were Muslim and Christian fundamentalists asking for constant holy war but they seldom were influential (p.63).

Gradually, the military momentum shifted in favor of the Northerners and by the end of the century, French and English trades were efficiently protected by modern warships. In the 1670s and 80s, Colbert obtained from both Maltese and Maghribi corsairs the renouncement to the right of ‘vista’ (i.e. the right to board and search a neutral ship in order to find enemy ware and merchants).

“Building a national trade policy [meant] a clearer separation between [nationals] and foreigners. In particular, by the end of the 17th century, the French stopped providing safe-conduct passes to Muslim and Jewish merchants. Thus local competition was push out of business as they did not benefit from the protection French shipping used to provide. To separate the communities more clearly, French subjects were not allowed any more to marry local women (p.65).

Protectionism was also on the rise toward the end of the century and the port of Marseille became off-limit for the North African merchants (p.66). Barbary traders faced both the hatred of the local population (due to the North African piracy) and the Christian corsair activities in the Western Mediterranean. As a result, the North African trade never managed to grow in the 18th century (p.67).

The king of France also managed to create a unified trade policy. Firstly the city of Marseille was occupied by the royal army in 1660 (p.68). But the national factors were still far from being the only at play in the Mediterranean, in particular the religious ones were still active as the papal protection granted to the Christian Greeks in the 18th century shows (p.69).

On the other hand, the French and papal restriction of Christian privateering (corso) allowed local trade to thrive in the eastern Mediterranean and successfully compete with the French caravane at the end of the 17th century.

References

Suraiya Faroqhi, ‘Trade: Regional, Interregional and International’, in Halil Inalcik with Donald Quataert (eds.), An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1994)

Sadok, B. La Régence de Tunis au XVII e siècle: ses relations commerciales avec les ports de l’Europe méditerranéenne, Marseille et Livourne (Ceroma, 1987)

Daniel Panzac, Les Corsaires barbaresques: la fin d’une épopée, 1800–1820 (Paris,1999)

Very interesting article! Good job. I do have a question though. Was there much trade between the Greeks of this period and the German/Dutch ports? I have read, but only scantly, that in the late 1200’s and again in 1400’s, many Greek merchants settled in Germany, Holland, and England. Can you shed any details on this? Thanks!