Gelderblom, Oscar (2005) “The decline of Fairs and Merchant Guilds in the Low Countries, 1250-1650″, Economy and Society in the Low Countries before 1850, Working Paper 1, 47p.

This article is available on line

Between the 11th and 13th century, during the Commercial Revolution, long-distance trade in Europe expanded rapidly thanks to organizational improvements such as fairs and merchant guilds (p.1). In fairs, merchants increased their chance to find business partners and benefited from the protection and the contract-enforcement abilities of the local jurisdictions. Merchant guilds were associations of traders from the same origin present in a foreign market and united in order to increase their bargain power with local authorities (p.2).

But after 1300, fair cycles declines and by “1500 all of Europe’s major commercial hubs (…) boasted permanent markets.” The multi-branch companies were less dependent on fairs than individual merchants to organize long-distance trade. Nonetheless, the case for late-medieval institutional change should not be oversold. Permanent markets existed before (Genoa, Venice), numerous fairs rose and thrived after 1300 (Leipzig, Medina del Campo; p.3), and trade guild-like corporations still organized numerous markets (East India Company).

To replace periodical fairs, permanent markets required a level volume and value of transactions seldom encountered in medieval Europe. Moreover, the rise of territorial states generalized a safe and efficient environment that feudal lords could only guaranty a few weeks at the time (p.4). Local authorities were also instrumental in the change of commercial practices as they provided much of the legal structure and all of the facilities supporting trade (warehouses, cranes; p.5).

Bruges

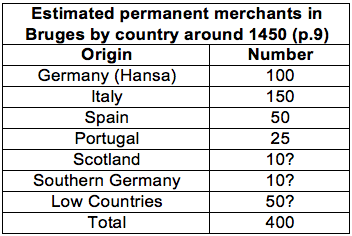

“Although [the] concentration of exchange in Bruges broke the rhythm of the fairs of Flanders and Champagne, trade continued to be periodical. Commercial transactions were concentrated in April, May and June, when the annual fair was held and the galleys from Venice, Genoa and Florence arrived.” From the 1350s to the end of the 15th century more than a dozen of foreign nations were formally represented in the city by trade guilds (p.6).

In 1253, the Hanseatic merchants – the oldest and biggest merchants community in Bruges – obtained a series of fiscal privileges and legal guaranties (p.10). Concessions were granted over time, often to specific communities. Ultimately, the various “nations” (i.e. trade guilds) were allowed to set and enforce rules for their own members (p.11). The count of Flanders and the city of Bruges agreed to relinquish part of their prerogative to the corporate jurisdictions (p.12).

The rise of the Brabantine fairs

“The only true competition for Bruges came from the fairs of Antwerp and Bergen op Zoom, established in the first half of the 14th century (p.17). (…) Compared to Bruges, there were fewer constraints on the business operations of foreign merchants: they were under no obligation to hire local brokers or unload and offer all their goods for sale”. But their promising start was compromised by political conflict (p.18).

A century later, “the growth of English export of broadcloth, and the refusal of Bruges to import them, brought English merchants [back] to Brabant”; the fairs also attracted merchants from Rhineland and Swabia and artisans from Brabant and Flanders (p.19). By the mid-15th century, the Brabantine competition was such that business in Bruges became stack during the fairs of its northern rivals; but Bruges retained the regional leadership not least because of its monopole on the financial service, which brought specie and rich consumers in town (p.20). But this advantage was lost in the 1480s when the conflicts between the city and the Maximilian of Austria forced all the foreigners out of town (p.21).

The growth of Antwerp’s permanent market

All the foreign merchants had moved to Antwerp by the early 1490s, the Hansa alone retained its kontor in Bruges. “In the first decades of the sixteenth century trade in Antwerp was still periodical. The high season fell between Easter and Withsun, when new broadcloths from England arrived together with the first shipments of grain from the Baltic, and the carts carrying silk, fustians, cupper, silver, […] from Southern Germany and Italy” (p.23).

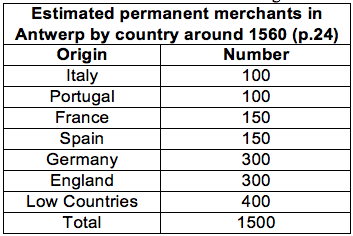

But the Brabantine fairs were gradually prolonged until they lasted two-third of the year; simultaneously the Antwerp eclipsed Bergen, which had lost any significance by the 1540s. The growth of trade in Antwerp created a permanent market; foreign merchants found it interesting to stay in town for the whole year. Tellingly, the number of resident alien merchants was more than double that of Bruges a century before (p.24).

Permanent infrastructure arose: unlike in Bruges where they stayed in hotels, many merchants bought houses; a bourse was established in 1531 (p.25) to centralize payments and exchanges. To stimulate transactions between unfamiliar merchants, the number of notaries was increase, the work of brokers regulated, the local customs codified (unlike what was the case in fairs, the Costuymen were applicable throughout the year) and legal courts became more available (p.26).

As a result, many nations simply did not feel the need to create corporate structures. The Habsburg rulers also proved particularly keen to protect the merchant community, for instance vehemently opposing any prohibition threatening Protestant traders. Yet, departure from the fair system was not complete, the English and Portuguese guilds remained active (p.27).

Amsterdam: open shop

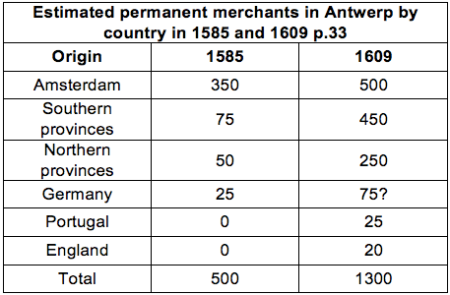

In the 16th century, Amsterdam emerged as the main supplier of shipping services to Antwerp and as the leading port for bulk trade (p.28). While the role of the city in the Dutch commercial network grew, the local government refused to charter any international fair, foreign staple, or merchant guild (p.31). The outbreak of the Dutch revolt forced most foreign and even Brabantine out of Antwerp, they naturally moved to Amsterdam. But the city still did not grant them any privilege, consequently the proportion of local merchants was abnormally large (p.33).

The city, on the other hand, proved particularly attractive for the so-called interlopers, those unincorporated individual merchants competing with the monopoles of the Merchant Adventurers, for example (p.34). The city adamantly extended existing facilities and created new ones: in 1611, the bourse was inaugurated (p.35), the number of notaries and brokers increased, postal services ameliorated, measures unified and ledgers accepted as legal proof (p.36). Although trade along ethnic lines continued, trust between unfamiliar merchants was generated by both governmental contract-enforcement procedures and reputation-based incentive (p.37).

Corporate restrictions only applied in the case of colonial trade (creation of the VOC in 1602, although it paradoxically allowed the rise of anonymous securities market). Symptomatically the trades with the Levant and Russia which were under strict monopoles in England, were only coordinated by semi-public bodies in Amsterdam (p.38). Even multi-branched firms seldom developed, “trade between individual merchants enjoying legal personality had become the norm”.

Conclusion

“Even if Bruges, Antwerp, and Amsterdam played similar roles in European long-distance trade between 1250 and 1650, there were marked differences in the organization of commercial and financial transactions in the three cities” (p.39). Privileges awarded to fairs and merchant guilds gradually grew less relevant and receded (p.40). The rise of the trade volume and value created permanent markets and the conditions local and central rulers could only enforce for a few weeks became the norm the whole year-long (p.41).

Tables