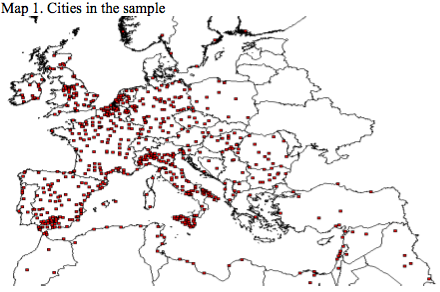

Bosker Maarten, Buringh Eltjo and van Zanden Jan Luiten (2008) “From Baghdad to London. The dynamics of urban growth in Europe and the Arab world, 800-1800”, CEPR.

Introduction

In this article, the authors wonder how did Europe rose from insignificance to global domination from 800 to 1800, while the relative importance of the neighbouring Muslim regions decreased. They try to define the “preconditions for the genesis of the modern economic growth” (p.3) and to understand the roots of the European modernity. When did Europe and the Arab world diverge (p.4).?

Theory

“Analyzing the location of cities (in particular near the sea), the structure of the urban system (the share of the largest and/or the capital city in total urban population), and the polity they are part of (city-states or republics versus Monarchies) we can find out what kind of forces are driving the urbanization process, whether we are dealing with producer or consumer cities, and therefore whether market forces or non-market transactions are behind urban expansion” (p.6).

Dataset

This study concentrates on cities with 10,000 inhabitants or more. Fifty-three reached that threshold in 800, and 603 in 1800 (p.7). The authors used a large number of published secondary sources to build their database.

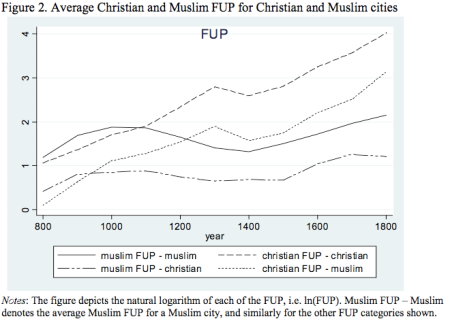

The authors used a gravity model to build their variable FUP (foreign urban potential). “The foreign urban potential of a city is defined as the distance weighted sum of the size of all other cities, where we measure distance in terms of relative transport costs” (p.10).

Preliminary results

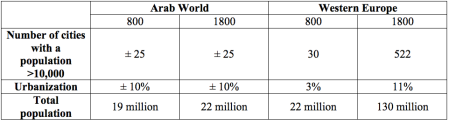

The authors found that the urban dynamics of the Arab World (Middle East/North Africa) and of Western and Central Europe were noticeably different and originated early on (see table above, p.13-14). The Muslim urban giants (Bagdad, Istanbul) led to a very high urban primacy ratio (up to 38% in 1700 and never less than 12%), while at the same time this ratio remained comparatively low in Europe (7% in 1700 and never more than 12%).

Analysis

Heritage

For Muslim cities being a port-town seem to have impeded their growth. The major urban centres were located inland. But being a hub or caravan road had a strong positive effect. The European cities were much more in the continuity of the Roman Empire: being a hub of Roman roads or a (arch)bishopric siege (sign of importance during the late Antiquity) had a clear positive effect on city size.

Borders

“Muslim cities have a strong positive impact on other Muslim cities, and the effect of Christian cities on each other is also positive and significant, but the interaction across religious borders is consistently negative! In the neighbourhood of (big) Muslim cities, Christian cities are significantly smaller than they would be under other circumstances, and the same, negative interaction effect applies to Muslim cities close to Christian cities! (p.17) (…) Trade across the borders of religions seems to be a problem – is constrained by high transaction costs.”

This fact may have caused the low urbanization of the Balkans (4.5% in 1800).

Overall it indicates “that Muslim and Christian cities formed two separate urban systems, which did not really interact with each other” (p.18).

The seas

Being located on the Atlantic was not an asset before 1300 (Vikings), but it changed from 1500 onward and became very positive between 1600 and 1800. The Baltic fostered the growth of its seaports from 1300 to 1500 but lost its impact afterward. The Mediterranean had been a factor of growth earlier (900-1200). For European cities, the sea after 1000 was always a significant bonus.

Capital cities

In the Muslim regions, being a capital city was very significant for growth over most of the period, the same was true for Europe in 800. But for Europe the importance of being a capital city decreased as the continent entered a period of weak and small states until 1000 (p.20). The bishopric sieges stepped in after 800 and became a strong factor of growth for the cities they were set in. This is an important evidence of how the Catholic Church took over as a political structure for the continent while the Carolingian Empire was crumbling.

The importance of being a capital city for a town’s demographic growth increased gradually after 1000 and finally became very significant in 1800 (p.21).

Chronology

The effect of negative feedbacks over the border of religions did not appear before 1100. This indicate that during the High Middle Ages, the European cities somewhat benefited from the economic boom of the Muslim world, while later the Muslim cities did not benefit from the rise of the West (p.27).

On the other hand the positive effect of interaction between Christian cities only appeared after 1000 “suggesting that these cities did not form a coherent system before 1100”. Indeed that is the period when the institutions typical of the productive European cities appeared (guilds, communes) (p.28).

Institutions

Acemoglu (2005) assumes that a city growth is to a large degree caused by the institutional environment of the country it is part of. The better the institutions, the higher the urbanization. Indeed feudal (particularly) and republican (i.e. the Netherlands and England after 1500) institutions did foster urbanization (p.29). As could be expected, big cities rarely grew bigger, specially in the case of Christian cities (p.31).

Finally the authors conclude that the Muslim cities’ little involvement in sea trade and dependence in caravan routes may have been their most notable weakness since 1/ unlike sea transport, caravans had a limited range of potential productivity growth, 2/ it depended heavily on security, thus Muslim cities growth was conditioned by the presence of big territorial entities (p.33).

The FUP between Muslim cities remained high during the Middle Ages and then tended to decline while between Western cities it started low and rose quickly; so it can be said that the Muslim cities were early on integrated in an efficient urban system but failed to improve on it.

“The solution to this apparent paradox is that indeed cities in the Muslim world (or outside the Latin West) tended to be consumer cities, which were part of states that manipulated large streams of income from the countryside to the urban areas. But these cities were also part of a relatively efficient system of (international) exchange, made possible by the introduction of institutions facilitating trade between the different parts of the Arab world. The efficiency of the network of trade explains the high levels of ‘static’ interaction found (the high FUP coefficient); the fact that the dynamic effects of these institutions were rather limited is related to the fact that these consumer cities were not based on some kind of equal exchange between town and countryside, but dependent on the coercive power of the state to extract a surplus from this countryside”.

On the other hand in Europe city growth led to more city growth (p.34).

Conclusion

“Summing up, the Arab world was in a way quite innovative (it adopted a ‘new’ mode of transport replacing the Roman infrastructure), exchange between Muslim cities was highly efficient, but at the same time these ‘consumer’ cities remained locked in into the basic institutions of states which were (because of their basically predatory nature) unable to generate long-term economic growth. The urban system that arose in Western Europe between 900 and 1300 was by contrast geared towards generating its own resources via market exchange; it was highly competitive, much less dependent on states (which were quite weak between 900 and 1300, anyway) and orientated towards long- distance trade via the sea. It was this ‘new’ urban system that generated the long term economic development that was characteristic of Western Europe in the millennium after 900” (p.35).

i have a problem with some of the information included.Their is no acknowledgement of the trade routes out of Ghana and Guinea.Arabic traders could not have manipulated the overland routes without some of the landlocked African Countries who were themselves traders. A few historical inaccuracies must be corrected.

Thanks for your comment but:

1. Neither Ghana nor Guinea were landlocked.

2. It has nothing to do with the problem at hands, they are writing about cities not trade routes.

Hi,

I wonder if you could tell me where/how you located the map of Paris that you include in this article. I was trying to find this map for a research paper I am doing and have only found a copy in a book that doesn’t reproduce too well and then this copy here. Is it the 1576 plan of Paris? Thanks!

Dear Alice

Unfortunately I’ve only recently started linking the illustrations to their sources. As a result, I have no idea of where I’ve got this one nor what it is exactly. Sorry.

B

The Paris map’s at http://historic-cities.huji.ac.il/france/paris/maps/braun_hogenberg_I_7_b.jpg – it’s from Braun & Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum vol.1 (1572) and apparently originates in a woodcut by Sebastian Munster first published in the latter’s Cosmographia (1569).

Re the paper, I remain unimpressed, principally because the Muslim urban population estimates rest on such shaky foundations as to be pretty worthless for gauging trends (some of the figures were rightly slashed between earlier and later drafts, indicating the authors’ recognition of the limitations of the data). At least they re-evaluated the numbers they’d been given, unlike Acemoglu & co.