Panzac, Daniel (1992) “International and Domestic Maritime trade in the Ottoman Empire during the 18th Century”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 24/2, 189-206.

Introduction

“A glance at a map shows what an important role the sea played in the vast empire of the Ottomans in the 18th century, linking as it did the three continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa that made up the Old World. The Ottoman Empire dominated not only the eastern Mediterranean but also the major part of the southern shore of the western Mediterranean, the Black Sea-a “Turkish lake” until the 1780s-the Red Sea, and part of the Arab/Persian Gulf. Geography gave the sea a decisive role in the trade that took place in the Ottoman Empire both internationally and domestically” (p.189).

International trade

Caravan routes were dangerous and commonly blocked by the conflicts between the Ottomans and the Shah. From the 1720s when it overtook its Persian rival of Bandar-Abbas to 1773 when it was definitely crippled by a outbreak of the plague, Basra dominated maritime trade with India; another route existed through the Red Sea which was particularly favoured by pilgrims on their way to Mecca. The most important imports from India were indigo from Aggra and later English Bengal, and muslins, printed calicos and other precious cloths (p.190). In 1785, imported 10 millions of livres tournois (£) worth of Indian products (almost as much as from Europe). On the other hand, the there was almost no Ottoman export to India and all the imports were paid in bullion. Most of the trade was in the hand of Armenian merchants and a sizeable portion was carried on European ships.

Trade with Europe was significantly more balanced. The Ottoman imports from Europe were mostly composed of manufactured products (mostly woollen, paper, etc.) and colonial re-export (cochineal, sugar, coffee). Europe imported mostly raw material from the Ottoman Empire (precious wool, silk, cotton, dyes and dried fruits; p.191). Noticeably European demand for silk dropped during the century (due to Italian competition). England for instance imported 77% less in value in 1761 than in 1701. On the other hand cotton export to Marseille increased by nearly 850% from 1700 to 1789. “The prosperity of the Ottoman textile industry is also verified by the increase in American dye imports” which grew 50% over the second half of the 18th century.

In the late 1780’s, the trade between the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe can be estimated at £ 110 millions. Trade with France alone grew from £ 12 millions in 1700 to £ 50 millions in 1789. In the 1780s, Panzac estimates that £ 11 millions transited through Salonica and nearly £ 60 millions through Smyrna.

“A second general characteristic of the Ottoman trade was the imbalance of exports over imports, with the exception of Istanbul, an enormous centre of consumption, which imported three or four times more than it exported. Exports from the main Ottoman ports exceeded imports (…). These important differences were made up by sending European currency, which went to pay for the chronic deficit the Ottoman Empire had in the Asian world” (p.192).

France was the main trading partner of the Ottoman Empire followed by far by England and then the Netherlands. The capitulation treaties between the Sultan and the European powers allowed the Westerners to benefit from a status of extraterritoriality in the Ottoman ports. Most of the contacts between European and local merchants were made through Greek or Jewish brokers (p.193). The French and the English (but not the Dutch) forbade local merchants, including their own brokers, to load merchandise onto their ships bound for their country.

Domestic trade

Trade and the sultan authority in the Red Sea area were very limited and only kept alive by the vicinity of the Holy Cities (and their port, Jedda). Around forty small ships attended to this mediocre trade entirely monopolized by Cairo’s merchants.

Most of the trade of the Black Sea was made up by the supply of wheat to Istanbul from Rumelie. All the merchants involved were Muslim and six of them controlled 40% of the trade. A fifth of the captains were Greek.

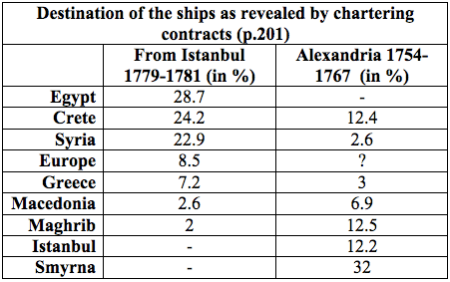

The Mediterranean linked numerous parts of the empire together and with the capital city; the route between Istanbul and Alexandria was particularly important (p.195).

Unlike what was usually the case in Europe, Ottoman merchants were not as a rule required to use Ottoman ships to carry their ware. The Ottoman ships were even a minority in most Mediterranean ports, they were commonly outnumbered by the French. In the 1780s, a half of the ships entering the port of Alexandria from Istanbul were European (p.196). European were mostly present on the high-value routes (p.197).

Maritime travel was significant, 19% of the European ships leaving Istanbul for another part of the Empire carried Ottoman officials on their way to their post or Christian pilgrims going to Jerusalem. Most ships left Istanbul empty as the city was primarily a huge consuming centre (p.199).

These constant trips even to and from far-away Maghrib show the unity of the empire and the economic interdependence of the various provinces. A quarter to a fifth of the charterers were from the various millets (religious minorities) of the Empire. Most of the Muslim charterers were Turks and even in Algiers and Alexandria they represented 40 to 50% of the charterers. Association between partners of different background were rare (p.200).

“The Ottoman Empire constituted a vast market where the same practices and norms were observed and where the diversity of the products and the needs were the very source of [the merchants’] activity” (p.201).

Conclusion

Domestic trade was by far more important than international trade, the latter represented around £180-200 millions by the end of the century (double the trade with Europe); in 1783 alone, domestic trade represented 77.25% of the £ 60.913 millions worth of merchandize that went through the port that year. Importantly, the Ottoman Empire consumed almost all its own industrial consumption such as the Syrian cloths; hence their absence in European ports cannot be associated with a collapse of the Ottoman manufactures (p.202).

Secondly, it appears that there was a class of mighty Muslim merchants in the Ottoman ports, who could charter 5, 10 and even 15 ships a year. During the 18th century, the Greeks and, to a lesser extend, the Armenians replaced the Jews as the most important minority involved in trade and finance. The Greeks commonly directly competed with European traders and after 1783, they even monopolized the trade with Russia.

Finally, it is important to underline the growing importance of the European trade that quickly developed during the century and profoundly penetrated the domestic trade (European textile represented half the value trade between Egypt and Jedda). Colonial imports also competed with domestic productions (coffee). The European also controlled 60 to 70% of the Ottoman domestic maritime trade. This gave them a key role in providing supplies for instance during the 1772-3 famine in Anatolia (p.203).

Only when European nations were at war with each others (mostly between France and England and later the Revolutionary turmoil) could Ottoman (mostly Greek) ships successfully compete with their foreign competitors. In the last quarter of the century however, military defeats weakened the economic integration of the empire. The monetary instability led to important trade in currency. Some Ottoman industries resisted well the challenged posed by the late 18th century but most finally collapsed during the dramatic events of the beginning of the 19th century (p.204).

I liked it and it helped me so much!!!! thanks